No doubt, I’m far from the only person thinking about climate change at the moment, what with the Paris Conference underway. Of course, as a conservation biologist, I’m often thinking about climate change (and sometimes driving my boyfriend crazy with my admonishments to turn off lights, water heaters and the air-con and even closing the faucet when he’s washing dishes with the water running).

As an urban ecologist, I’m also thinking urbanisation and global climate change. So, given the current context, I think it’s worth dedicating a blog post to this topic – how exactly are the two linked?

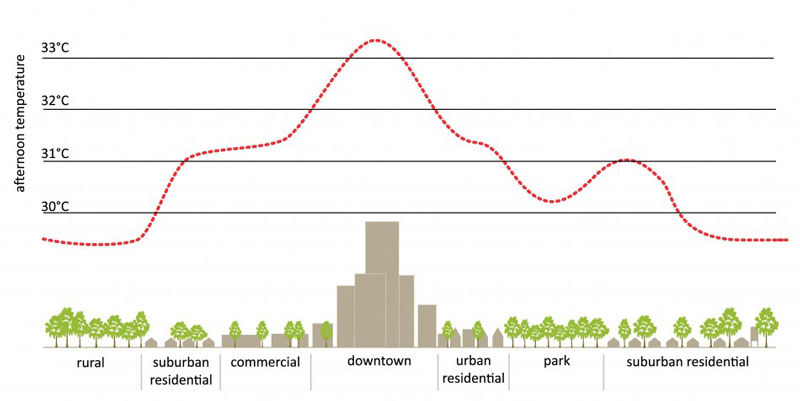

First of all, there is no doubt that urban development produces profound changes in climate at the local level. The term “urban heat island”, or UHI, refers to the well-documented phenomenon whereby a city is noticeably warmer (air and surfaces) than the surrounding landscape. The intensity of the UHI is variable – it depends on latitude, biome, season and time of day, among other factors – typical temperature differentials are about 1-3ºC, but they can be as high as 12ºC.

The UHI arises mainly as vegetated areas and bare soil are converted to urban land cover (pavement and buildings). The cooling effect of vegetation (via shading and evapotranspiration) is lost, and the albedo of the land decreases as dark, built surfaces absorb more sunlight than plants do. Other forces at work include urban canyons, which describe the geometry of a city, in which tall buildings essentially trap heat in their walls and prevent it from radiating back into space. In addition, the concentrated burning of fossil fuels (e.g., for transport and electricity) in cities is a source of anthropogenic heat.

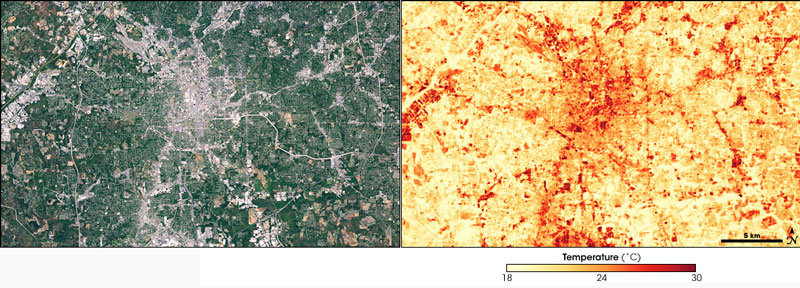

These paired satellite images, taken in 2000, illustrate the UHI in Atlanta, Georgia. The image on the left is essentially a photo, in which green areas are covered by vegetation, grey areas by built surfaces (pavement and buildings) and brownish areas by bare soil. The image on the right shows land surface temperatures (with a scale). You can see that urban development increases surface temperatures.

There is evidence that because of the UHI, cities create their own weather, often characterised by increased cloudiness and rainfall in cities and areas downwind. But the UHI doesn’t just affect the weather – it also has profound impacts on human well-being and the environment.

These are heat exchangers of air-conditioning units in Singapore. As urban temperatures rise, so does our discomfort and, therefore, our use of air-conditioning. This not only increases release of GHGs, but also generates heat, further exacerbating the UHI. Photo: Peter Morgan. Own work – Creative Commons. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

In winter at higher latitudes, the UHI decreases the need for heating and so results in energy savings. Unfortunately, this benefit is outweighed by the fact that the UHI exacerbates heat waves, which are becoming more frequent due to global climate change, and vice versa (i.e., heat waves exacerbate the UHI; check out this study – not only very cool, but also very easy to understand, with simple writing and excellent figures). As a result, demand for air-conditioning and refrigeration increase by 1.5 to 2% for every 0.6°C increase in Tº. And deaths due to heat-related illness are higher than expected in urban areas.

The UHI also exacerbates smog, mainly by provoking an inversion that prevents polluted urban air from mixing with clean air from the surrounding area but also because elevated air temperatures increase the rate of ground-level ozone formation.

Water quality is negatively affected by the UHI, which causes thermal pollution. Paved surfaces not only stay very warm, but also increase the amount of surface water runoff. They transfer their heat to stormwater, which enters inland water bodies, where it very quickly raises water temperature by up to 4ºC. Because many aquatic organisms are very sensitive to water temperature, these rapid changes can be very dangerous. For example, brook trout experience thermal stress and shock when the water temperature changes by more than 1-2°C in 24 hours, and their occurrence seems negatively affected by urban land cover in a watershed.

Urban populations of European blackbirds (Turdus merula) are becoming more sedentary. Eventually, this change in migratory behaviour could lead to speciation. Image: Juan Emilio, Own work – Creative Commons. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

On the other hand, the UHI is associated with extension of the growing season at higher latitudes. Researchers are documenting changes in the onset of flowering and fruiting (which typically advances) and of winter dormancy (which is typically delayed). In turn, these changes increase the period of availability of food to animals, some of which are altering their distributions and/or migratory behaviour as a result. Some birds may even lose the tendency to migrate altogether.

Overall though, the impacts of UHIs on wildlife are not very well-studied yet, and this is an area of research that deserves more attention. In a way, the UHI is kind of like a microcosm of global climate change, and a better understanding its effects on habitats and organisms may help us make better predictions about the effects of global climate change.

Do UHIs contribute in any substantial way to global climate change? This question is hotly debated by some. In fact, climate change skeptics (who, unfortunately, continue to hold sway over some politicians) have claimed that UHIs have skewed the data collected by climate monitoring stations, and that the apparent global warming trend is really just a measurement of increasing UHI effects, and so we don’t need to reduce GHG emissions (never mind that the science unequivocally links global climate change to our emissions of GHGs).

In contrast to this assertion, one study cited in the IPCC 4th assessment report examined 270 stations worldwide, and found that warming trends in minimum temperatures from 1950 to 2000 were not enhanced on calm nights, which is when UHIs are most evident. Other studies found that the current warming trend is equally clear at rural stations far from cities and at urban stations. Finally, a study that modeled climate responses from 2005 to 2025 revealed that UHIs are minor contributors to warming, compared to GHGs.

Ultimately, the UHI has little, if any, direct impact on climate change. It happens at the local level, whereas climate change is a global phenomenon. Nevertheless, mitigating UHIs is still important. After all, urbanites (human or not) are expected to feel the effects of climate change especially keenly, and already a great deal of extra energy is being used to combat the effects of UHIs.

Let me reiterate (in case it isn’t immediately obvious) that urbanisation is, in many ways, one of the best things to ever happen to humanity. It improves access to jobs, healthcare, sanitation, housing and education. Cities could even have a positive impact on global climate change, because, by housing dense human populations within small areas, they could increase the efficiency of resource-use.

Unfortunately, the potential benefits of urbanisation to climate change are not being realised, and current patterns of urban growth and consumption are unsustainable. Just think: per capita ecological footprints (including emissions of GHGs) are highest in cities and in the most urbanised nations, partly because of over-reliance on imported goods and services and urban sprawl. Cities currently contain more than half of humanity (54 %, to be exact). And despite occupying a tiny fraction of all the land on Earth (less than 3 %), they consume more than 75 % of its resources. When you consider that by 2050, we expect the global urban population to attain 72 % of all people on Earth, well, I’d say that we really need to change our patterns of urban development.

Despite the negative implications of urbanisation for climate change, I remain an optimist (how can you be a conservation biologist otherwise?). It’s the start of day 2 of COP 21, we’ve got a far more committed Canadian contingent than we’ve had in the past (kudos to Justin Trudeau for inviting all the provincial Premiers and for vowing to take tough action), and a number of nations have urbanisation-related agendas for the conference. Therefore, I’m hopeful that the outcomes will include guidelines for urban planning and development that will help Canada and the rest of the world accommodate future, rapid urban expansion in such a way that it mitigates rather than exacerbates our impact on the global climate.

Sending wishes of peace, health, safety and determination to all COP 21 participants.

Joanna