1. The spathe—a 5th floral structure.

Most flowers have a four-part anatomical arrangement. The two central whorls (layers) of reproductive parts include a pistil (a sticky stigma borne on a style leading down to the ovary) surrounded by stamens (filaments bearing anthers, which hold pollen grains). The outer whorls are sterile, accessory parts: petals attract pollinators, and sepals protect the flower bud and attach to the receptacle. Eastern skunk cabbages (like many species in the family Araceae) also have a spathe. This leaf-like structure forms a cloak-like chamber around the entire spadix (what we call the aroid inflorescence, or spiked flower cluster).

2. Ladies first.

Having separate sexes is rare in flowering plants. Most are hermaphrodites (with bisexual flowers) or monoecious (separate male and female flowers on the same individual). And most of them are self-incompatible—they can only be fertilised by pollen from another individual. This creates a challenge: how to avoid having their own pollen land on their stigmas. One adaptation for that is dichogamy—their male and female flowers mature at different times. It most often manifests as protandry (stamens mature first). But eastern skunk cabbages are protogynous. The spadix first bears tiny, white female flowers (only the style and stigma are easily seen; as in the photo on the left) and then, tiny, yellow male flowers (which look like a collection of stamens; as in the photo on the right).

3. It missed the “spring flowers” memo.

Growing up in Quebec (and indeed, until very recently), I always thought the first plants to bloom each year (snowdrops, trilliums, etc.) emerge in early spring. Nope. Undeterred by even the thickest blanket of snow on the ground, skunk cabbages bloom in winter.

4. It acts like a mammal.

As a bat specialist, I work with mammals whose thermoregulatory abilities put all others to shame. So, naturally, I am drawn to what you might say is the bat of the plant world; a species that uses its metabolism to raise its body temperature above ambient—a behaviour called thermogenesis. And while many other aroid species are thermogenic, eastern skunk cabbages take it to the extreme, raising their body temperature ≤35ºC above ambient!

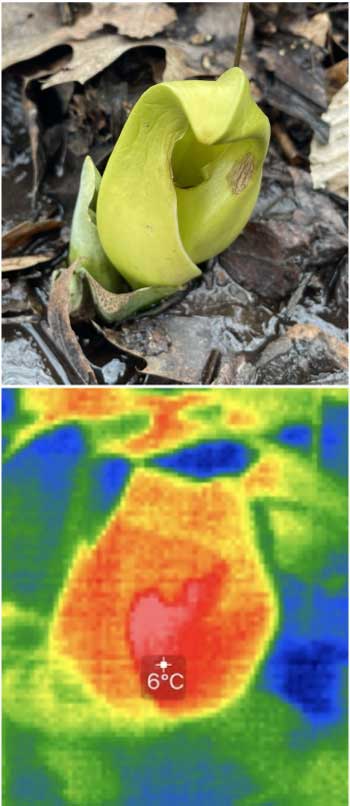

Look at the photos of the same skunk-cabbage spathe at right. The upper one is in full-colour; the lower one was taken with a basic thermal camera (which is not very accurate, so ignore the 6ºC label). The red-to-white region at the centre is the thermogenic spadix, whose heat is detectable even through the spathe tissue.

The complex mechanism behind thermogenesis involves “short-circuiting” the last step of the electron transport chain in cellular respiration, so that instead of yielding a molecule of energy (ATP), the process gives off heat. It occurs in female spadices and is mediated by the alternative oxidase (AOX) enzyme. To learn more about thermogenesis and see some awesome photos of eastern skunk cabbage (better than mine!) see out this website.

A long-standing question is why these plants evolved thermogenesis. There are four (not mutually exclusive) hypotheses proposed to explain this. They suggest that thermogenesis: (1) wards off cold damage to the plant; (2) lets the plant bloom in winter and occupy an otherwise empty ecological niche; (3) enhances the transmission of the floral scent to attract more pollinators, and (4) creates a warm, cozy environment for pollinators.

Oh, and our team members agree that our study plants emit no scent until they are damaged, when we detect a pleasant, skunky smell.