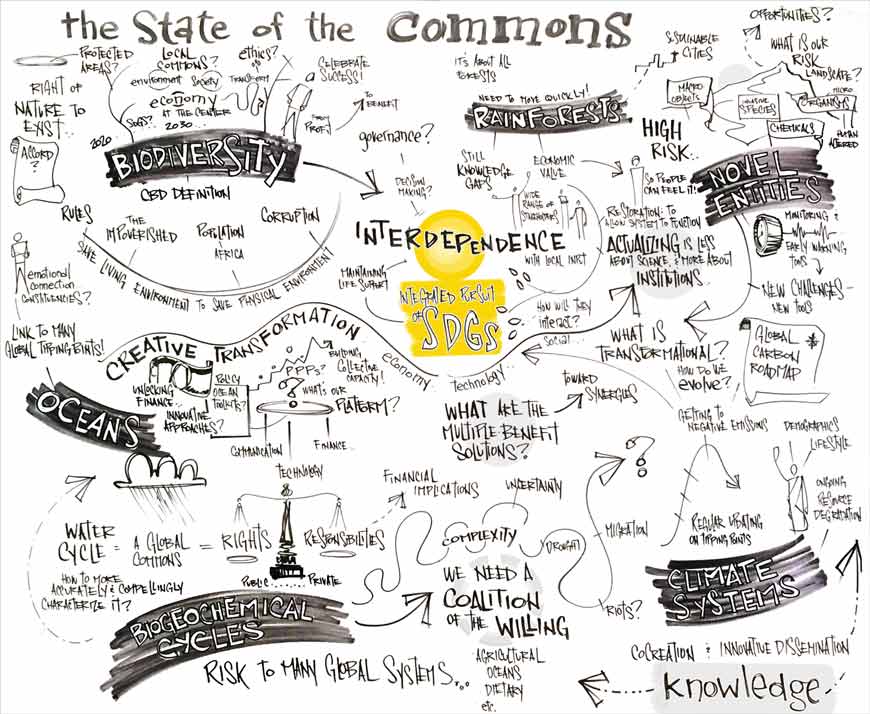

Look at this mind map (from the GEF site). It conceptualises the state of the Global Commons. The thing I kept thinking about during Ragupathi & Creelman’s podcast, David Wiley’s Ted Talk and Dave Cormier’s primer on MOOCs, and while reading Chapter 11 in Teaching in a Digital Age.

I mean, other thoughts came up too, especially about my own open ed practices now and going forward. And maybe I’ll get to those in a future post. But here, I’ll focus on how this topic aligns with the core of who I am and what I believe. Not just as an educator. Not just as a conservation biologist. Not just as an environmentalist. As a person.

In my year 1 environmental-studies course, I use a class activity to introduce students to the Tragedy of the Commons. If you’re unfamiliar with it, I’m talking about the reality that while many resources are (ethically speaking) freely available to all, the selfish pursuit of personal gain essentially renders them inaccessible to many. Especially to people who need them most. And the more money you have, the greater your ability to pursue your own personal gain and deplete these resources. And by ‘you’, I mean individuals, corporations and governments.

Manifestations include phenomena such as land & water grabbing and the consequent removal of rights from previous users of the resources, often indigenous and other marginalised peoples who can scarcely afford alternatives. They include corporations polluting soils and waters that people rely on for their daily activities and livelihoods, resulting in massive harm to communities (e.g., the well-known Love Canal case). It all boils down to environmental injustice.

Well, throughout my consumption of the ONL materials for this topic, I couldn’t help thinking about how similar this is to the elitism of HE. It occurs on a global level, i.e., restricting access to students who can afford it or who have high enough grades to earn scholarships, while leaving most people, especially in less affluent jurisdictions, in the dust. After all, there’s a clear link between affluence and educational attainment, including via the practice of grade inflation. And we in Singapore and at NUS aren’t immune thanks to deeply entrenched practices, such as high admission cutoff scores, the “buying” of access to more prestigious primary and secondary schools, etc.

Trouble is, this (priority access to HE education for elites) undermines sustainability goals given knowledge that as a population (especially girls and women) becomes more educated, its total fertility rate declines. And curbing population growth sooner rather than later is key to our survival. But also (and perhaps more fundamentally), my ethics tell me money shouldn’t buy knowledge. That knowledge is part of the Global Commons.

For me, the most powerful message in all the materials was delivered by Johanni Larianko, 11.5 minutes into the podcast: “If knowledge is power, then that knowledge should be distributed as widely as possible.”

Take another look at the mind map. Specifically at the bottom righthand corner. Clearly, I agree that “knowledge should be considered a common good and be accessible as openly as possible”.

Hi Joanna,

Thank you for an inspiring blog post. I agree, knowledge and education should be open and accessible to all.

Best regards,

Maria, group 11

Thank you Maria – your post made me think as well !

Hi, Joanna. Nicely written blog. I am particularly intrigued by how you view Open Education and sharing of education resources from the angle of the “Tragedy of the Commons” (Hardin, 1968). I have been thinking about how open education can work best when every player is equally responsible, equally contributive and so on. Your blog post and its link to “Tragedy of the Commons” help me to articulate it. And I’m now wondering whether there is an optimum level of knowledge sharing; what what affects it.

Great sketch, by the way.

Hi Andi (hope that’s the proper way to address you – correct me if it’s not).

Thanks for your comment and kind words. And I agree, that is an awesome sketch – some people are so talented, no ?

To be honest, I’m conflicted about this whole topic. I mean, I stand by what I say in this post. But at the same time, I have reservations about the Open Ed concept. One is the apparent need to make content universally applicable (so anyone can understand and use it). This doesn’t sit well with my belief that educators must put content in context if we want to make it relevant to students’ lives. Another is the lack of accountability on the part of the learner. Like, I design assessments so that my students acquire useful skills and apply what they’re learning. How do Open Ed learners demonstrate acquisition of skills and knowledge if nobody is grading their work ?

Those are just two of my issues, but I’m not sure the tension between my misgivings and my beliefs that (1) knowledge doesn’t belong to anyone and (2) we must help others, especially in the places where most people live and where people most yearn for a better life, to achieve a decent standard of living if we’re ever going to solve the environmental crisis.

Really looking fwd to the webinar this week – hopefully these issues will be raised.

J

I really like how you draw a parallel between tragedy of the commons and open learning. And I wanted to take it a step further!

The thing about tragedy of the commons is that it is used to make the case that without top-down regulation or privatisation, human greed will ultimately prevail, and the commons will be degraded. But in Elinor Ostrom’s work (‘Governing the Commons’) she gives examples of how the tragedy of the commons isn’t an inevitability, and that bottom up and community governance can co-manage common pool resources sustainably. (This is a good read if you haven’t already: http://www.dpi.inpe.br/gilberto/cursos/cst-317/papers/ostrom_sustainability.pdf)

This makes me think of today’s webinar where Alistair talked about how no institution could have ever created Wikipedia – it’s open approach made such a resource possible. I guess what I’m sitting with is the question, How can Ostrom’s work on governing the (ecological) commons help us understand governing the (intellectual?) commons? Personally, I think her design principles for common pool resource might really resonate! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elinor_Ostrom#Design_principles_for_Common_Pool_Resource_(CPR)_institution

Might be something for me to ponder when I walk away and think about my own blog post…

Hi Bekki,

Thank you very much for your thoughtful comment.

Very interesting and thanks for the link ! In fact, I agree with you and I teach my environmental-studies students the tragedy of the commons to illustrate not the need for top-down governance, but rather for concern for collective wellbeing if we’re going to steer our way out of this crisis.

However, my stance on Open Ed is increasingly murky and I’m quite torn. In my PBL group, we had a discussion that made me see how certain aspects of Open Ed (namely, the dominance of English & technical requirements) can exacerbate privilege and the consequent inequitable distribution of knowledge. Polling my current students revealed some very real reservations on their part about the fairness of their educators openly sharing what they are paying good money for.

Ironically, considering that I’m enrolled and engaged in ONL, I’m questioning the ethics of Open Ed (something I didn’t expect to be doing). I too have much thinking to do, including about how to reconcile my commitment to environmental and social justice with my obligations toward my students.

Ah interesting – in our group we delved into the ethical piece as well. But we never got around to talking about the language piece (funny, since for most of us English is not our native language). I so often forget about this piece because English is my mother tongue – I guess that’s how privilege works, hey?

Hi Bekki,

Absolutely.

It’s interesting you say that. Many students in my intro to environmental studies this year seem very interested in the issue of privilege, so we’ve talked about it a lot. One of them, Rachel LIM, has been putting together an incredible assignment, in which she reflects very deeply on the barriers to people living more sustainably. A couple of her earlier posts deal with privilege and (shameless plugging for a student I’m super proud of) I invite you to check it out – and do feel free to interact with her or any of my students, whose blogs are listed on this page.

Have a great day – J

Thanks Joanna for taking the time to put your thoughts into words. Separating out the content and context has certainly made it clearer for me to reflect on how I feel about open ed, and I agree that as educators our expertise is in contextualising the content for our learners. I am not sure the open ed can achive this.

Thank you Kirsty for taking the time to visit my website and read my blog post. This is a topic I am quite conflicted about, and it’s a conflict I don’t think will be resolved anytime soon. In addition, polling my current students reveals that they have significant reservations about Open Ed.