Cheryl YIP Yi Xiu, Bachelor of Environmental Studies student – AY 2017/2018

Knowledge of and attitudes toward bats in Singapore

Negative attitudes toward bats are hardly unusual. Indeed, bats are reviled in various societies, including in Singapore (SG), where they are among the most common animals that residents complain about to government agencies. To some extent, this may reflect fears related to disease transmission. After all, bats are natural reservoirs of some serious emerging infectious diseases (EIDs), and there’s evidence that some fears and negative attitudes toward animals are grounded in our evolutionary history, which predisposes us to avoid or fear animals that may harm us.

But the real risk of disease transmission from bats to humans is super low. Most people never come into contact with bats, and disease prevalence in bat populations is usually low. Besides, many EID pathogens, such as the coronaviruses that cause SARS, MERS and COVID-19, didn’t move from bats directly to humans, but rather infected intermediate hosts first. A more important cause of general malignment of bats is likely how they are represented by the media, their association with evil and persistent myths about them.

Well, that’s a problem. I mean, of all orders of mammals, bats are among the most diverse and are the most ecologically important (see this blog post). Yet they also remain poorly understood and face high rates of endangerment (see this blog post), especially in SE Asia. Plus, while bats do receive some legal protection in certain jurisdictions, that’s not the case in most regions, including SE Asia.

Clearly, societies and governments aren’t prioritising the protection of bats – maybe due to widespread negative views. That’s why many bat specialists do outreach. But, while outreach aims to raise support for bat conservation, for it to be effective, we must understand what our target audience knows and feels about bats and address issues in culturally-appropriate ways.

In this context, I’m launching a global study of knowledge and perceptions of bats (and the underlying drivers) with international collaborators, and Cheryl did the pilot, focusing on adults in SG.

She carried out a sequential exploratory mixed-methods study. By mixed methods, I don’t just mean collecting qualitative and quantitative data and then analysing them together. Students in my lab who do mixed-methods research generally apply Pat Bazeley’s definition of mixed methods (from this study)…

“… involves the use of more than one approach to or method of design, data collection or data analysis within a single program of study, with integration of the different approaches or methods occurring during the program of study, and not just at its concluding point.”

In other words, there is deep and purposeful integration between the qualitative and quantitative aspects of the research. In this case, Cheryl conducted focus group discussions (FGDs) to obtain qualitative data, which she then used to develop questions for her quantitative survey, which she administered via semi-structured interviews or online.

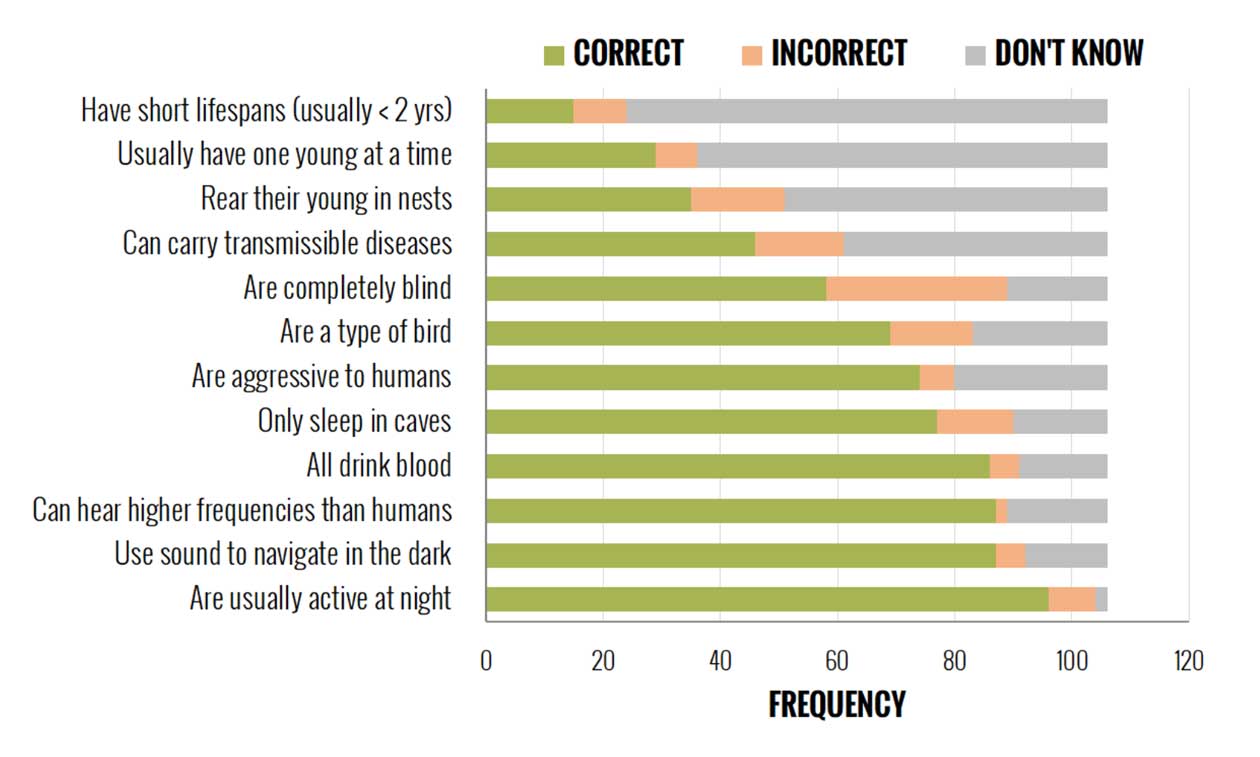

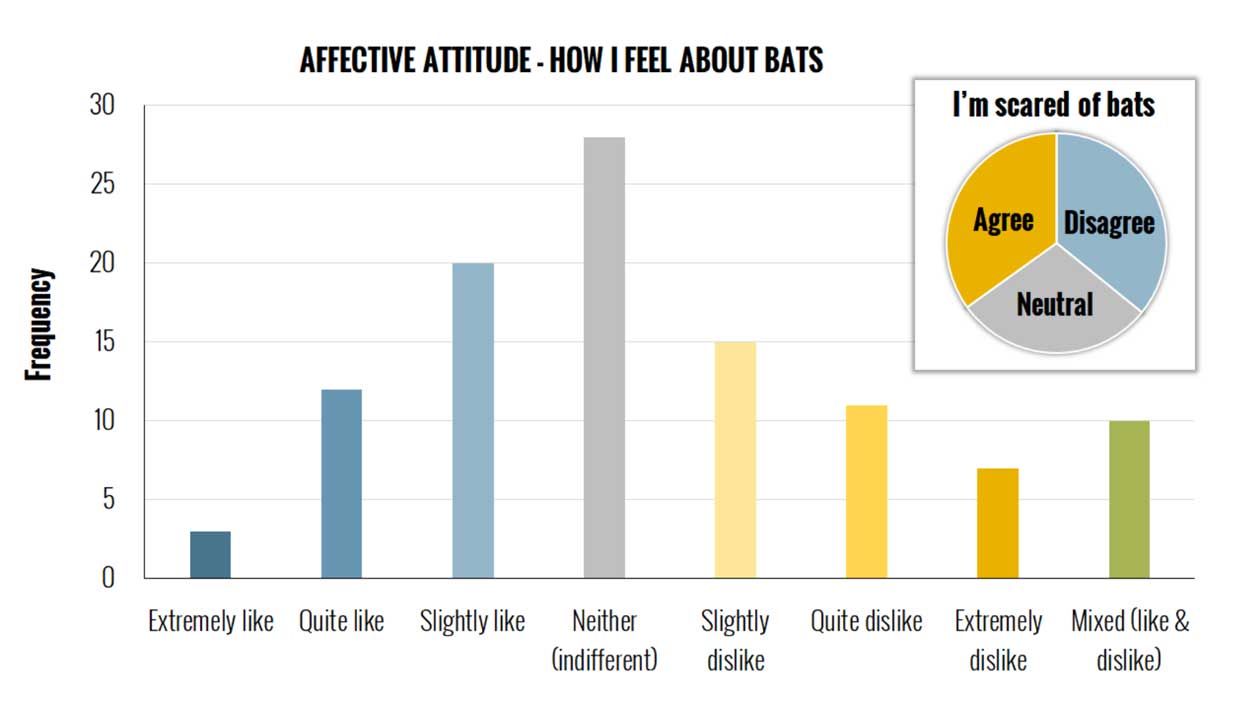

The upper chart depicts responses to knowledge questions – most respondents got more than half correct (the one they had the most trouble with was the “bats are blind” myth). The lower chart shows affective attitudes (what I feel), and this population tends to hold neutral to weakly positive ones (but look at the pie chart and note the prevalence of fear).

As for cognitive attitudes (what I believe is true), most respondents agreed that bats are part of the natural environment but disagreed that they’re attractive or charismatic. Still, less than half agreed with downright negative statements that bats are disgusting, dangerous and a nuisance. To get at the behaviour aspect, Cheryl measured social attitudes (what I expect from society). Most people agreed that bats have the right to exist, are an important part of Nature and deserve conservation but less than half support allocating government funding to that. Finally, those who own pets and had positive prior encounters with bats were more likely to have positive cognitive attitudes.

This study, repeated in many locales worldwide, could provide useful data that will make bat-conservation outreach more targeted and culturally relevant.