PANG Yong Ting Roanna, Life Sciences Major – AY 2017/2018

People who feed Singapore’s street dogs – who and why?

Many urban and peri-urban areas around the world have populations of free-ranging dogs (FRDs), which include owned, stray and feral individuals. A huge body of evidence documents the negative impacts of FRDs on ecosystems and human health. These include predation on, disturbance of and introduction of diseases to native wildlife (e.g., this study) and the risk of attack on and introduction of diseases, e.g., rabies and other zoonoses, to humans.

Like many settled areas in Asia-Pacific, Singapore (SG) has a sizeable population of FRDs – in this part of the world, they’re commonly referred to as street dogs because, well, they roam the streets. And in SG, despite ongoing and government-sanctioned control efforts, including trap-neuter-release-manage (TNRM) and trap-removal (TR, or culling), the population is likely maintained by a combination of ongoing mating and abandonment (additions of stray dogs). Plus, there is widespread subsidisation – meaning, these dogs are fed by people.

From 2016 to 2018, I was the local Principal Investigator on a study of these street dogs – a joint effort with University of Queensland. Our overall goal was to answer basic questions about the population, i.e., elucidate its demographics, distribution, movement patterns and ecology.

Roanna’s project focused specifically on 33 diverse stakeholders who feed the dogs – this was the first study on the social dimensions of feeding. Using a semi-structured interview approach, she developed a profile of feeders to answer these questions.

- Where are dogs being fed?

- How often are they being fed?

- How many feeders are there?

- What is being fed (type of food and quantity)?

- Why do feeders engage in this behaviour?

- What are their perceptions of the population control strategies currently employed in SG?

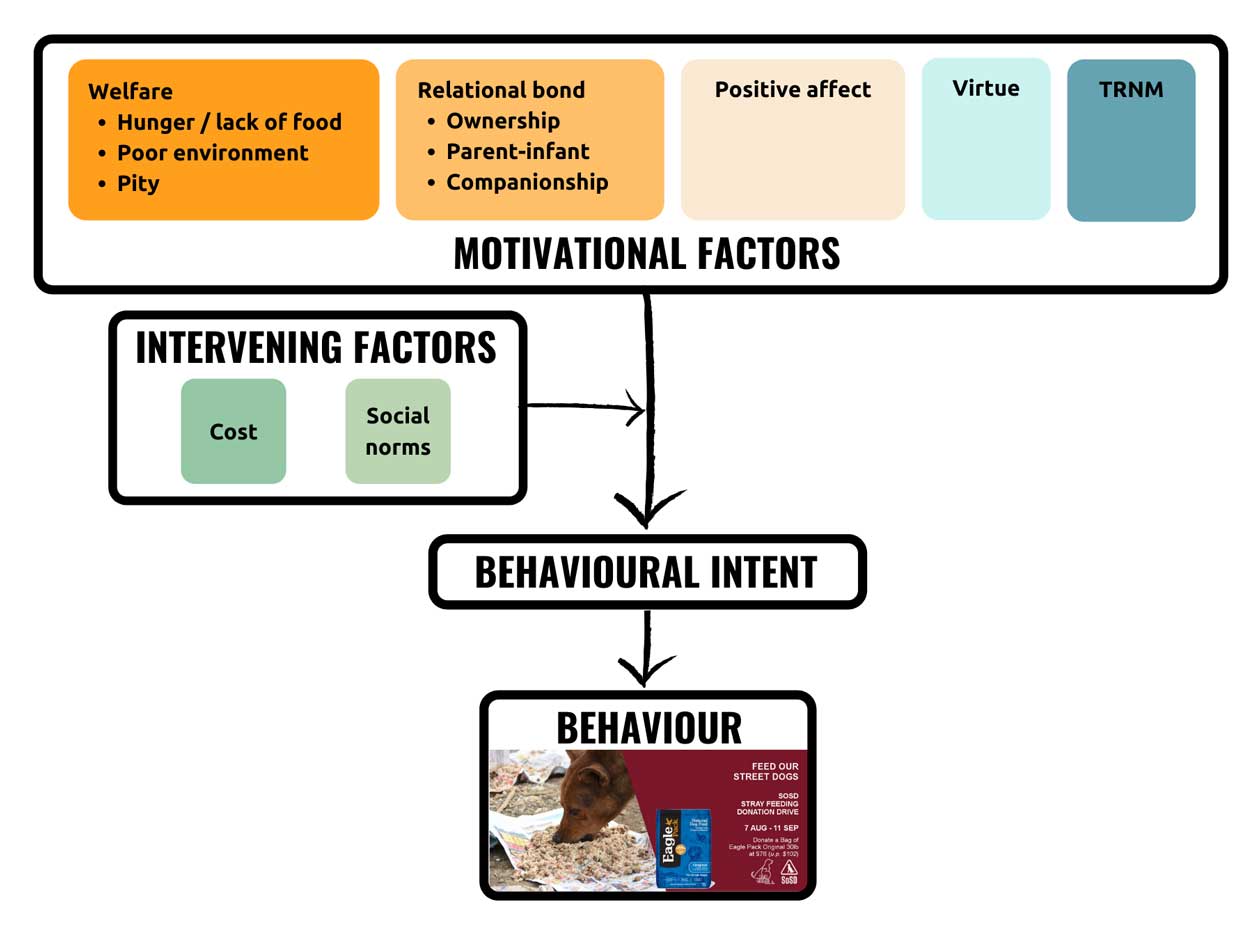

She used Grounded Theory (GT) strategies and qualitative data to develop a conceptual framework that theorises the relationship between motivations, intervening factors and feeding behaviour, represented in the figure below. Here, the most influential factors are motivating ones, such as concern for dogs’ welfare and the dog-feeder relationship – these matter more than any intervening factors that hinder feeding. Roanna also identified four types of feeders: dedicated, workplace, casual and hired and described their views on the government and its current management efforts.

This study suggests certain actions for better dog management. Three in particular include: (1) collaborating with dedicated feeders when it comes to sterilisation efforts, (2) increasing communication between feeders and the government and (3) educating feeders who don’t feed dogs in a responsible way. Future studies could also use Roanna’s exploratory work as the basis for a questionnaire to target a larger sample of feeders in SG or elsewhere.