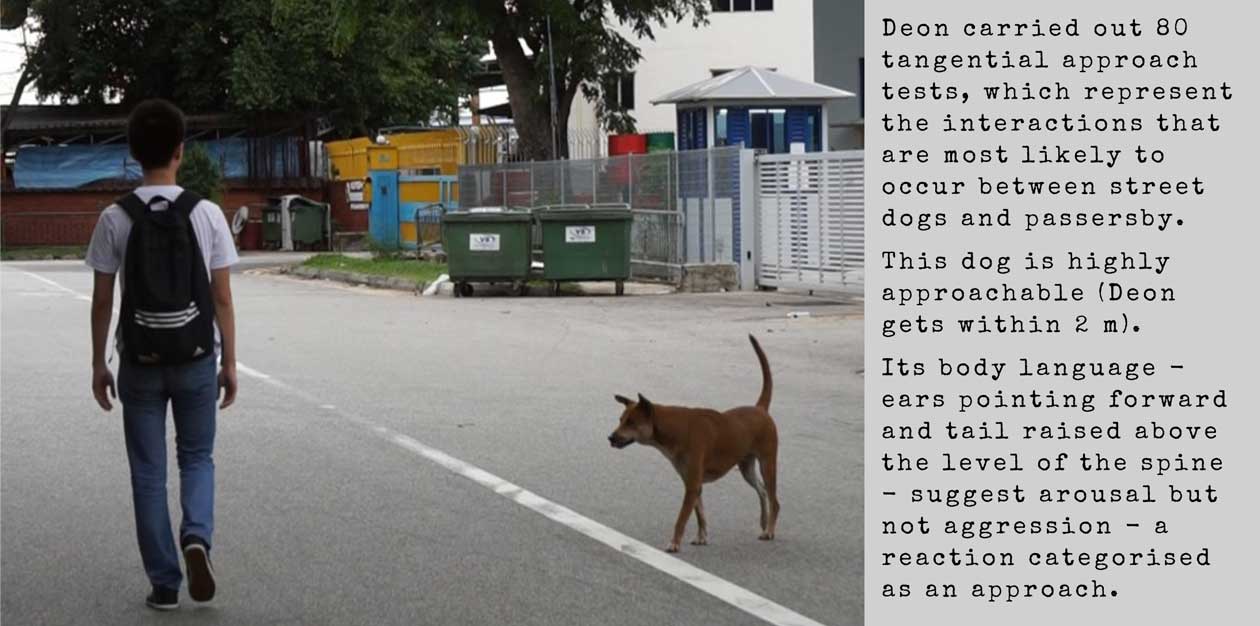

LUM Wen Hao Deon, Bachelor of Environmental Studies student – AY 2016/17

Behavioural responses of free-ranging (street) dogs to human approach

Free-ranging dogs (FRDs) are found worldwide and, unlike owned and restricted dogs, roam about freely. In Singapore (SG), FRDs include owned dogs that are let out on their own, lost or abandoned pets (strays) and feral individuals, but in Asia, they are all commonly called street dogs. And while street dogs may be of value to locals for various reasons, the freedom to roam creates public safety and health concerns. One is the risk of attacks on humans. Attacks are rare but can lead to serious injury or death, transmission of zoonotic diseases and fear and mental distress.

And so, many countries actively manage their FRD populations through diverse initiatives, although the main method of control is usually shaped by societal perceptions. SG has a street dog population (indeed, studying this population – its dynamics and ecology – was my main research project for three years), and there are occasional attacks in different sites. The government manages the dogs through a combination of trap-remove (culling), trap-neuter-release-manage (TNRM) and promotion of responsible ownership, with local animal welfare groups stepping in with programmes of their own, namely TNRM and adoption, to avoid culling. This is an emotionally charged issue, with animal welfare advocates often pitted against the government and decrying its use of culling.

However, the choice of management method should really be grounded in a solid understanding of the risk of attacks. That’s where Deon came in. He set out to identify some of the risk factors for aggression. He conducted tangential approach tests on 80 dogs in four sites and documented their responses. Most dogs either remained neutral (41 %) or fled (40 %) – only 6 % reacted aggressively. Only 16 % of dogs vocalised (e.g., barking, growling). He was able to get within 2 m of most dogs (54 %). As for the most influential intrinsic and extrinsic factors, approachability is higher for dogs that are male, neutered, alone and in industrial sites. Group size matters too – for every increase by one individual, dogs are twice as likely to vocalise and 1.6 times as likely to be aggressive than to flee. But site is the best predictor of all – dogs in industrial sites are the least approachable (in terms of how close he could get and the likelihood of a flight response.

Overall, his results suggest a real, but low risk of aggression for pedestrians. Deon hypothesised that aggressive behaviour is linked to territoriality, which is encouraged by subsidisation (feeding), and that indiscriminate feeding discourages tolerance of approach. And even though intrinsic traits and group size contribute to variation in their responses to a stranger’s approach, their behaviour is also strongly influenced by human behaviour.

After working as a research assistant in the lab of Prof Ryan Chisolm, a theoretical ecologist, and quantifying extinction risk for birds and mammals, Deon was accepted (on scholarship) to University of Manchester, where he will start his PhD in September 2021.