LIM Kai Ning, Life Sciences Major – AY 2018/2019

Impacts of drones on bats

Conditions in the airspace are way more variable and dynamic than those of the lithosphere or hydrosphere. So, the adaptations to withstand these changing conditions tend to include high versatility (like how birds and bats can change the shapes of their wings). But only recently have these animals had to contend with human intrusions into and alteration of the aerial habitats, such as via anthropogenic structures, lights and aircraft – all pressures that present risks of collision and disturbance – pressures they are not adapted to.

A new ‘invader’ is the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), or drone. The drone industry is growing massively, especially in cities, where current and future applications include recreational use, urban mobility, security and urban planning. This is true in Singapore (SG), where drones also have unique practical purposes (such as to deliver mail) and are used in research (such as to inspect tree crowns). Thus, there is no reason to expect anything but an ongoing increase in the use of drones and, hence, a more crowded airspace.

There is some evidence of negative effects on animals, including the ones that researchers and practitioners sometimes use drones to monitor (e.g., bears, birds). But otherwise, ecological impacts remain essentially unknown, including where bats are concerned, even though drones are already used to study them. So far, there are no reports of bat-drone collisions, but drones do produce noise in the range of frequencies used by bats to echolocate. Besides, they have lights and moving parts that bats can presumably see, and therefore react to.

Kai Ning worked in parks in SG, where she used acoustic monitoring to determine whether the presence of recreational drones affects echolocating bats. The approach was to compare bat activity between nights with and without drones. She was unable to detect an effect from her quantitative data.

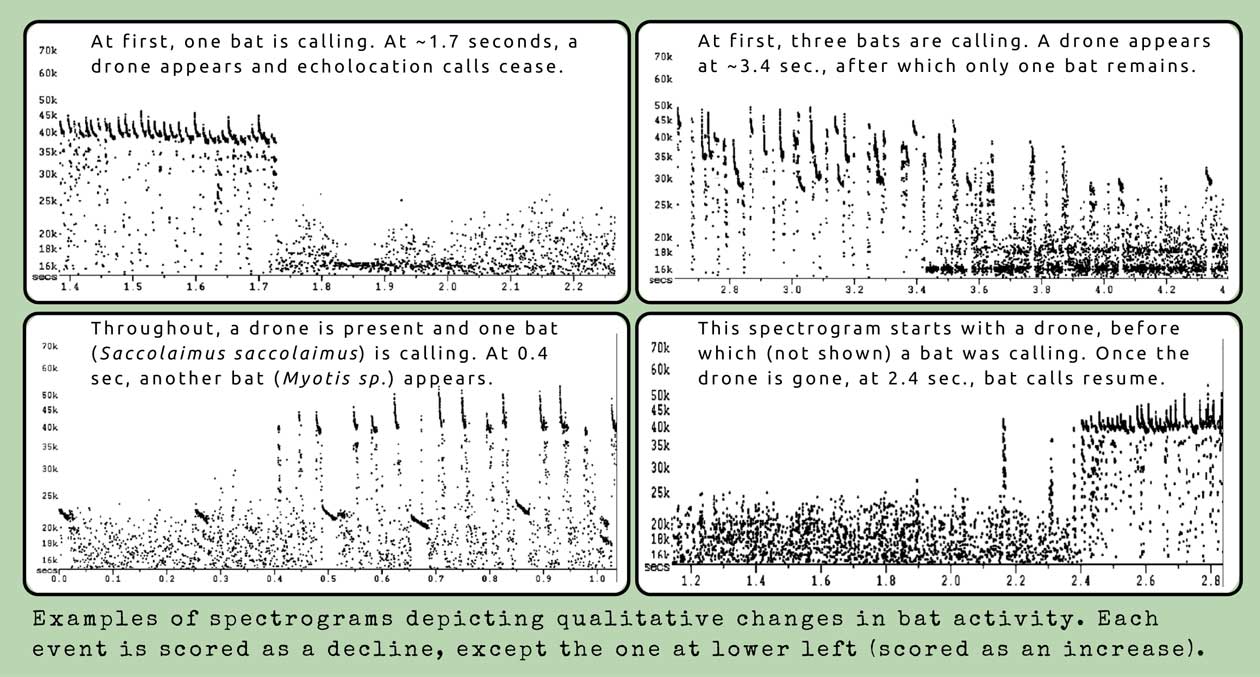

However, qualitative examination of spectrograms revealed that in 77 % of drone events, there is some reduction in echolocation calls. For example, calls cease when a drone appears and resume and resume after it leaves (as shown in three of the image panels below).

Such observations suggest some disturbance. What is unclear is whether bats leave the area or stay but stop calling. Either way, this represents a potential energetic cost to the aerial insectivore because this mode of hunting typically relies on echolocation.

Although SG seems like a good place to ask this question, what with all the bats in its green spaces and drones so popular, the regulatory context turned out to be less than ideal. By that, I mean there are so few places where people can fly their drones that it is virtually impossible to find a green space where a researcher can set up proper treatment and control conditions without the interference of other hobbyists. And to me, an experimental approach is what’s needed, which means this study may be best done elsewhere. And if a thermal imaging camera could be used too, then it would be possible to more clearly describe the response of bats to the presence of a drone.

Kai Ning is now working with NParks, more specifically on the issue of pest birds. To download a copy of her thesis, click here.