Johnathan WONG, Bachelor of Environmental Studies student – AY 2019/20

Invasive snails and their potentially zoonotic nematode parasites

Certain species of African land snails have been introduced in diverse locations, where some have become quite invasive. One is the Giant African land snail (Achatina fulica) – one of the world’s most notorious and nefarious invasives. Where it forms large populations, it can cause substantial damage to plants, including economically important crops. Another issue is that this snail is an intermediate host for Angiostrongylus nematodes, which can cause serious disease. For example, the rat lungworm Angiostrongylus cantonensis can infect humans who ingest it – the most common antecedent of eosinophilic meningitis. Well, in cities, where there are plenty of rats and other natural hosts, the snail can thus facilitate the transmission of the potentially lethal infection to humans (as in the 2018 sensational story of the Australian man who died eight years after eating a slug on a dare).

The snail has been present in Singapore (SG) for some time and two Angiostrongylus species (A. cantonensis and A. malaysiensis), prevalent in neighbouring countries, may be in SG too. But the distribution and prevalence of infected snails are unknown. What is known is that in SG, some people collect and consume these snails, which presents a potential health risk – one that increases if snails aren’t prepared properly or there’s hand-to-mouth contact. Plus, with rising public engagement in urban gardening and farming, people could ingest nematode larvae on inadequately washed produce.

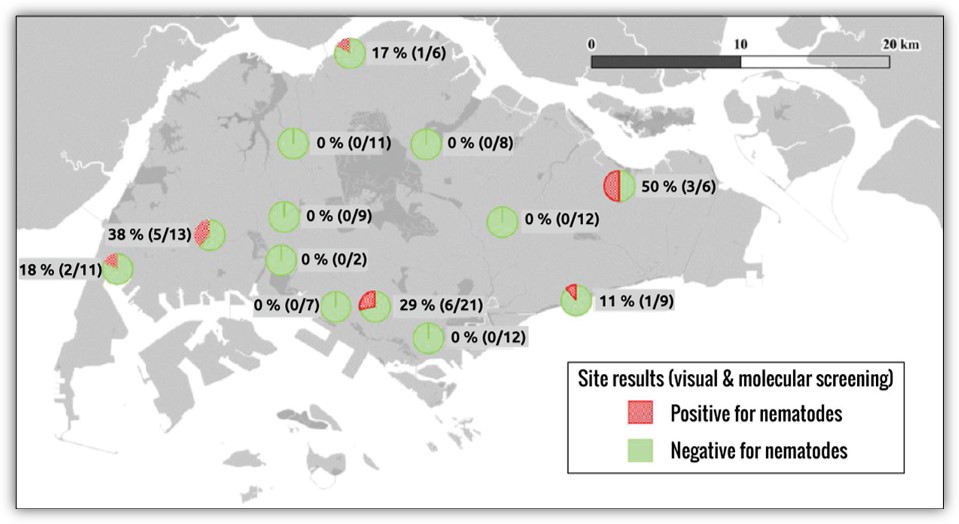

Johnathan aimed to shed light on this issue by collecting snails at 13 sites across mainland SG and screening them for nematodes using microscopy and NGS-based DNA barcoding (which he performed in the lab of Prof Rudolf Meier). He also collected citizen science data to estimate the population density of snails.

He detected nematodes in 18 of 120 snails – these individuals came from six diverse sites, where prevalence ranged from 11 to 50 % (that’s what the map shows). Island-wide infection prevalence is estimated at 15 %.

All the nematodes were identified as A. malaysiensis, a new species record for SG. But this shouldn’t be taken as an indication that A. cantonensis is absent – especially because its life history is nearly identical to that of A. malaysiensis. Another finding of importance is that the intensity of infection (parasite load per infected individual) is unrelated to the size of the snail (an indicator of age).

Given that infected snails occur in diverse sites (including parks, industrial areas and residential estates), this parasite seems well established in African land snails, and so is probably enzootic in local rodent populations too. And the high human usage in these sites suggests potential risk of zoonotic disease – one that may warrant stepping up wildlife surveillance, especially because SG doesn’t have programmes to monitor gastropod-borne parasites and because other gastropod species may harbour these and other potentially pathogenic nematodes. There may also be reason to implement control efforts and public education campaigns, bearing in mind that snail size does not predict parasite load and disease risk increases with the number of nematodes ingested.

After completing his BES degree, Johnathan worked as a research assistant in Prof Rudolf Meier’s lab at NUS, working further on DNA barcoding projects. But his interest in public health being durable, he starts his PhD at Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School in August 2021.